Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza: the Politics and Poetics of Disappearance

par Marc Lenot

Article published at fragments liminaires : Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza (Les Presses du réel, 2015), reproduced with the authorization of the autor. The book can be adquiere here.

I’m writing this text in a house I haven’t lived in for long, that I’m still getting used to, where my “writing room” resembles a den, a cave hollowed into the adjacent hillside, a place where my view of the sunny outside world is rather like that of a man in hiding, on the lookout, not a hunter but a watcher. And I think to myself that this viewpoint is rather like that of the observer in an air of welcome, the artist’s latest series, which she completed during her residency at the Centre photographique d’Île-de-France in Pontault-Combault and which opened her exhibition fragments liminaires (“preliminary fragments”), in this same Centre, in Spring 2015. Most of the images in the series appear to have been taken from inside a hole, from the depths of a cave; they’re partially or completely ringed with black, as if the visible image of the world they show is framed by this dark non-image. And the visible itself – forest, field or prairie – seems uncertain, blurred, unsettled, traversed by indistinct, unidentifiable forms that almost vibrate, so that the first time I saw an image from this series, this optical trembling so confused me that I thought it was a video. To create these images, the artist captured online videos, (mostly1) posted by North American vigilantes who had hidden automatic cameras at the Mexican border to detect clandestine immigrants, fugitives who cross this no man’s land to reach what they believe to be the Promised Land. She then blurred the outlines of the migrants, leaving only a fleeting trace, a barely visible shadow of a human spectre, a ghostly being floating between two worlds, between two lives: is what is visible really seen? Is what is shown here actually real? These images are far from neutral: they provide a shelter for the illegal immigrants, shielding them from the arm of the law; they represent a position, a discourse, a place and a history. Like all the artist’s work, these images deal with visibility and absence, history and memory, displacement and territory.

Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza was born in Ecuador and has lived in France for thirteen years. She belongs to both countries: one peripheral, long colonised and fantasized, multicultural and proud; the other central, arrogant and nostalgic, Cartesian and dominating. She is an artist who keeps watch on the world, constantly moving between these two places, physically, mentally, oneirically, poetically, artistically. Her work, which I have followed since she left the Beaux-Arts in 2006, takes various forms – photographs and videos, performances and installations – but always shows great coherence and profound unity: each piece can easily be seen as a fragment of a major work in progress, gaining in substance and refinement with every step. Together, we envisaged this book and the exhibition that it accompanied not as a hasty retrospective of the work of a young artist, but as an ensemble of “preliminary fragments” on the threshold of its future promise.

The withdrawal and protection through invisibility that these images offer the clandestine migrants are also present in the anonymous figures of people without rank, without name, without identity papers. Day after day, the artist erases their images from these photographs of “extras” – people who are just part of the scenery, undifferentiated as a group and individually insignificant, deprived of all singularity – removing them from the official history (untitled (extras)). When all that remains on the sheet of newspaper is a white shadow where the “extra” once appeared, she keeps the resulting fragments and parings, which now bear the traces of the image, in small flasks, like reliquaries or memorials to the unknown “extra”, and carefully aligns these containers as if they were in a columbarium where the individuality of each person – who now has a number, if not a name – becomes an object of memory. From this time on, the “extra” has a role, acquires singularity and significance, ceases to be an anonymous actor and begins to play the poetic, metaphorical figuration of the people.2 Such concealments, such withdrawals are constructions of the invisible, drawings of absence. Another drawing of absence is the large white wall in front of which, the first time I saw it, I saw nothing (mirage(s) 2. imaginary line (equator)). When you come from a region that bears the name of a concept – recognised, but having no tangible reality – how can you make this invisible visible, how can you invite the viewer into this snare of perception, into this confined, infrathin space between imagination and image, between latent and manifest? It is nothing but a long trace made by a white eraser on a white wall, but it is sufficient to reveal signs where none were expected, to create an impossibility of seeing that interrogates the status of the image itself. “Remembering to forget, erasing to draw again”3. Already, at the beginning of her artistic career some fifteen years ago, Peñafiel Loaiza encased objects in wax, withdrawing them from the world, hiding them from view, reducing them to the state of memory, concept or even “hidden noise” (collection of secrets) [fig. 1].

This work with disappearance and resurgence is also apparent in the obliteration of the Word, in the programmed suppression of words, or rather in their transfer to another place. She does this with her country’s sacred text, the Constitution – or rather the eighteen constitutions that Ecuador had between 1830 and 1998, constant attempts to define itself which she reads in public but backwards (countdown4), thus creating a remarkably strange oral space, both incomprehensible and familiar, somewhere between republican majesty and popular diversion. Above all, she does it with a book that is essential and revelatory for her compatriots and has provided the raw material for several of her pieces: Ecuador, by Henri Michaux, the account of the 30-year old author’s initiatory travels in the Andes (in 1928). The artist removes its trace with her magical erasing pen (preface to a cartography of an imagined country), and as the disoriented reader/viewer vainly attempts to grasp the text, to urgently seize it, this un-writing is a poignant, almost unbearable sight – the frustration of being unable to read, of being confronted with the vanishing of words, of being forced by this breakaway of meaning to venture beyond the visible. Another time, on the contrary, her ink-stained fingers imprint themselves on a page of the same book, caressing and anointing it, causing the printed words to reappear (cartographies 1. the crisis of dimension). Elsewhere, it’s a poem (Chambre d’hôtel, “Hotel Room”) that has become unstable and invisible, stencilled on paper with loose charcoal and gunpowder: perhaps it will be scattered by an ill wind – just as, 65 years ago, the people of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (the poem’s author) were scattered – unless, one day, the conjunction of the powder and a flame will blow it up (déclaration de flamme). In another piece, soot-blackened sheets of glass hide the pages of books, showing only a few enigmatic phrases whose meaning, both present and absent, we struggle to reconstruct (sous rature5).

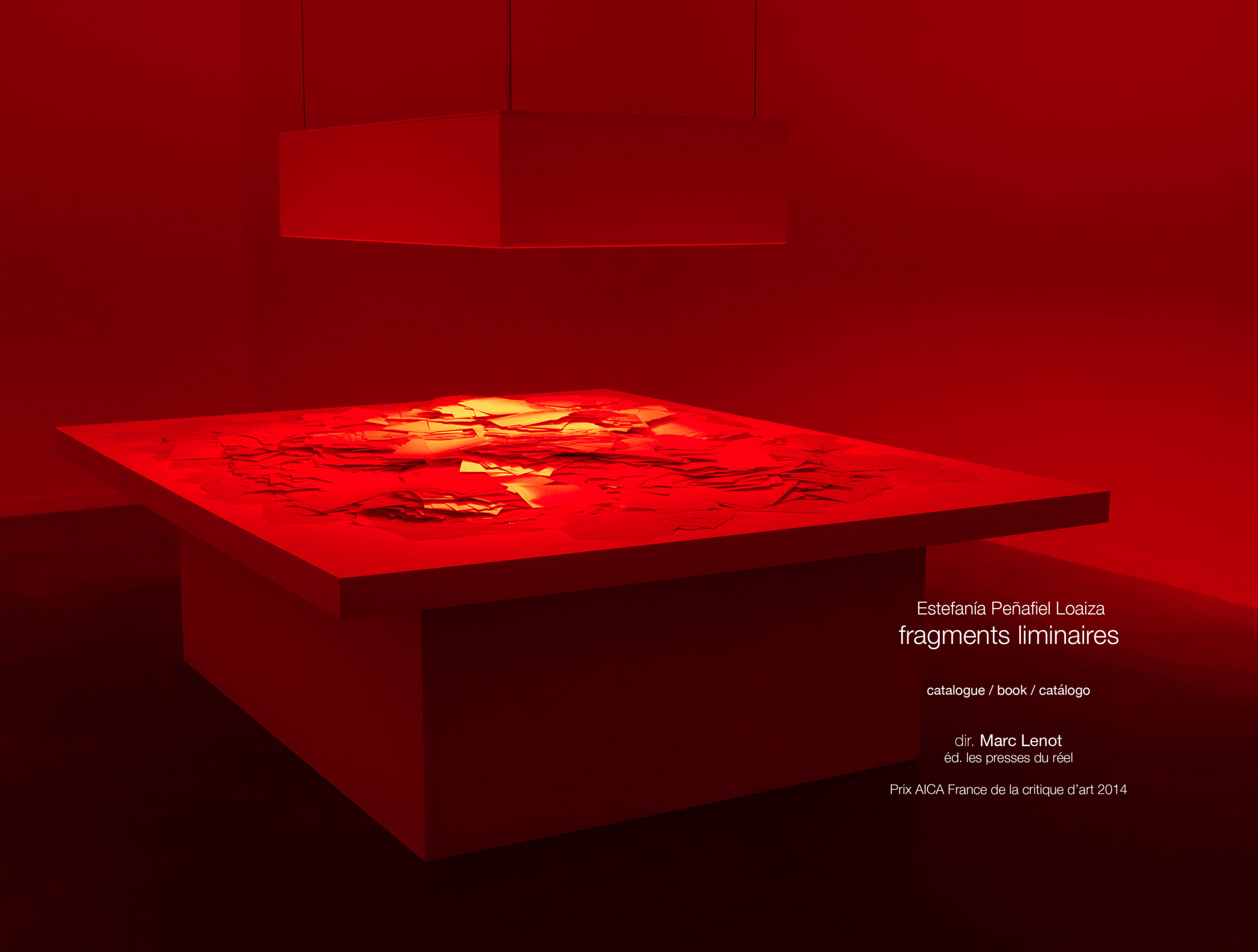

The dialectics of disappearance, or at least of its possibility, pervades the work of Peñafiel Loaiza. Words are stencilled by the mere imprint of her dermatoglyphics on windows or mirrors and can only be seen in a certain light, by squinting at them or blowing on them, words that tell the secret history of places – mirage(s) 3. Armenia – or of the world – epiphany. Images are projected on phosphorescent screens where they survive for a few moments like ghosts – no vacancy; the invisible cities 3. the spark (Vincennes 2008) –, images showing a hidden, rejected, forgotten reality. A photograph is rendered invisible by too strong a light – fiat lux – one of the Sonderkommando photographs of Birkenau, an unbearable image, the only photographic trace of the reality of the camps, that some would have denied the right to exist.6 Shots of burned-out buildings are exposed in red light, making it impossible to distinguish the slightest detail – cherchant une lumière garde une fumée –, shots of riots in suburban ghettos, from 2005 to the present day. And each work deals with oblivion and memory, the refusal to see, repressed history, impossible sights, the fight for the persistence of memory: in view of the disappearance of History, how can it still be revealed, as image and as truth? The artist’s most striking piece in this vein is no doubt angelus novus: on sheets of paper pinned to a black wall-hanging, a hand tirelessly writes and erases the words “history repeats itself, History repeats itself, histories repeat themselves, Histories repeat themselves”: the angel of Klee and Benjamin,7 the angel of History turned towards the catastrophe of the past and propelled backwards towards the future, presides here over the confusion between history and History and their repetitive combination. For Peñafiel Loaiza’s work is deeply rooted in History, and consequently in politics. It contains the reflection of our world: the Armenian genocide and that of the Jews; the Conquistadors – a certain idea of paradise 1. este oro comemos (according to Guamán Poma de Ayala); the Algerian war – from one gaze to the other (hasta mañana Rebeca, espero que tú no vas a olvidar); the Commune – the invisible cities 1. the awaiting (Paris 1871); our globalised society, social apartheid and total repression, and rebels of all kinds – wind from the East – from the anonymous of the North to the illegal immigrants of the South. It is obviously never a literal, lampoon-like transcription but, on the contrary an evocation that I would describe as poetic, which conveys on another level what rational language alone could not express.

Confronted with these shreds of History, the work of Peñafiel Loaiza is not one of destruction, but rather of displacement, transfer to a new territory where the vestige of the deconstructed image can subsist differently: the residues from the erasing of the “extras” are preserved in memorial urns; the spirit of places lives on in fleeting inscriptions on windows or the leaves of trees; sound is preserved, re-transcribed in the engraving of a sonogram on books coated with wax (seismographies 3. bookbindings); the base of a former guillotine – still standing in a Paris street, though nobody knows it – is preserved with a cast that gradually crumbles and disintegrates (present, imperfect). Likewise, a text by a humble chronicler of the history of an Occitan village is re-transcribed on the walls of the local manor (the end of the mine (according to René Gayraud)), and an Argentine tale by Eduardo Galeano, after being translated from Spanish into English then from English into Hindi, is reinterpreted graphically in the form of a traditional comic strip by Indian artisans (las palabras andantes (fumure)): gradually, with each displacement, history – History – is conserved and transposed. At a previous exhibition at the Crédac art centre, a former factory in Ivry-sur-Seine, in keeping with her habit of creating pieces related to the venues in which they are exhibited, she took imprints of the “skin” of the factory floor, thereby producing a double-sided palimpsest, a vestige of the past activity of the place and a sign of its present life, a passage between these two temporalities (the episodic space). In this way, the artist draws a new cartography of the world, linking places laden with meaning: her works are (almost) always inscribed in a specific geographical and territorial place, in a particular country, a particular village, with, of course, the lines of the horizon, of the equator…

Sometimes, the place is particularly significant, like the Administrative Detention Centre in Vincennes, a place of exclusion, never shown, where foreigners “in an irregular situation”, as the saying goes, are detained before their expulsion, sometimes rebelling against this by setting fire to their prison; then Peñafiel Loaiza’s ghostly images, projected on a phosphorescent screen, subsist for a few moments as if to preserve, a little while longer, the hope that will inevitably fade (the invisible cities 3. the spark (Vincennes 2008). In another heterotopia,8 in a former military fortress overlooking the city of Grenoble – a place of defence and control, designed to discipline and punish9 – she produced a video installation in which Foucault’s text, transcribed in braille, was silently “read” by a blind man’s fingers, with no sound but that of the rubbing of his fingers on the paper and his breathing, accentuating a renewed tension between the need to see and its impossibility (not a single place in there that does not see you). An exhibition held in South America (en valija, Cuenca, 2013) was contained within a suitcase, composed of works that were light in weight but dense in thought. At another event (“Le Monde Physique”, a collective exhibition at La Galerie, Noisyle- Sec, in 2011) she put prières d’insérer [fig. 2](little cards bearing quotations about travelling and moving) inside the pages of library books; maybe one day ordinary readers will be surprised to find them and will put them in other books – or perhaps they will remain forever in books that everyone has forgotten.

Working without grandiloquence, with deliberately humble means, Peñafiel Loaiza constantly shifts perspectives, countering conventional representations, surprising and disturbing the mind and the eye, destabilising the relationship we thought we had with the image, the sobriety of her means reinforcing the poignancy of her message. Rather than showing images, she reveals signs, questions representations, interrogates memories, brings out the sediments of History, and constructs what could be called a phenomenology of the visible. My sight is thus transformed, unsettled: the visible appears but the real remains invisible, ungraspable. Am I not, after all, in a cave, faced with shadow-mirages?

Lisbonne, April 3, 2015

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

After his studies at the École Polytechnique and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Marc lenot (Saint-Étienne, 1948) worked as an economist and a strategy and recruiting consultant before reinventing himself as an art critic in 2005. For the last ten years he has written an online reference blog on contemporary art, Lunettes Rouges, published by Le Monde (http://lunettesrouges.blog.lemonde.fr/). In 2009, he obtained a Master’s Degree from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales with a thesis on Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý. He is currently completing a thesis on contemporary experimental photography, under the direction of Michel Poivert at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. He was the first “digital” member of AICA in France, and in March 2014, competing with nine other French art critics, his oral presentation of the work of Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza won him the AICA France Prize, awarded by an international jury. He divides his time between Lisbon and Paris.

NOTES :

-

Other videos are of the border between Israel and Palestine.

-

On this subject, see Georges Didi-Huberman, Peuples exposés, peuples figurants, Paris, Minuit,2012.

-

Title of Sophie Rosemont’s article in the journal Mouvement (June 2008) on Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza’s exhibition at the Galerie Paul Frèches in Paris.

-

Online at www.cuenta-regresiva.art

-

The title obviously evokes the Heideggerian concept, taken up by Derrida, of the impossibility of a definition other than by the ambiguous duality of present-absent.

-

See the polemic between Georges Didi-Huberman and the friends of Claude Lanzmann in G. Didi-Huberman, Images malgré tout, Paris, Minuit, 2004.

-

Walter Benjamin, Thèses sur la Philosophie de l’Histoire, Paris, Denoël, 1971.

-

Michel Foucault, Les Hétérotopies – Le Corps Utopique, Paris, Lignes, 2009 [1967].

-

Michel Foucault, Surveiller et Punir, Paris, Gallimard, 1975.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________